September 9. 2022

The Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa got a significant victory Wednesday in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin, where a judge ruled that Enbridge Energy and its Line 5 pipeline had trespassed on Reservation lands and unjustly enriched itself since 2013.

In the 56-page ruling, Judge William Conley said the Band was entitled to financial compensation. He stopped short of granting the Band’s request that Enbridge immediately cease pipeline operations across its lands.

“An immediate shutdown of the Line 5 pipeline would have widespread economic consequences,” and have significant implications “on the trade relationship between the United States and Canada,” Conley wrote.

According to the ruling:

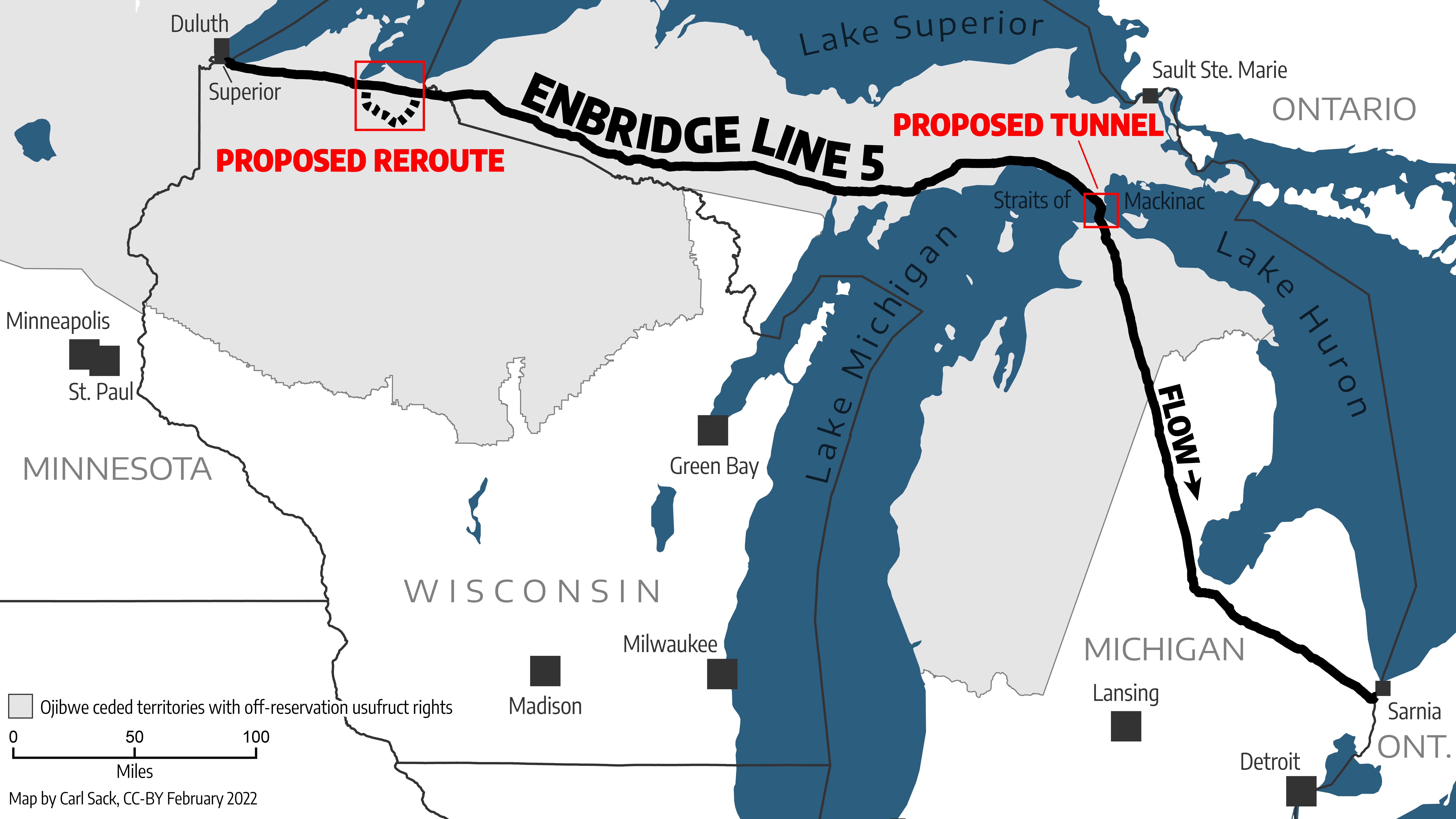

Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline carries 23 million gallons of crude oil and natural gas liquids daily across northern Wisconsin. The line starts at the Superior Terminal, where Enbridge Line 3 (now called Line 93) ends. Line 5 continues east through Michigan to Sarnia, Ontario.

Early history

Enbridge (then Lake Head Pipe Line Company) built Line 5 in 1953. It crosses 12 miles of the Bad River Reservation.

In 1952, the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs (“BIA”), “granted Enbridge Line 5 a single, 20-year easement to cross Reservation lands. It covered all the parcels on the Reservation owned either by the Band or by individual Indians. In the early 1970s, the BIA renewed that easement for another 20-year term,” expiring in 1992.

Negotiations to renew the easement began in the early 1990s.

Enbridge wanted an easement that ran longer than 20 years. The BIA told Enbridge it wouldn’t approve such an easement, but encouraged Enbridge to negotiate directly with the Band.

Two new easements negotiated

Land within Bad River, like other reservations, has multiple owners. The Dawes Act of 1887 forced private land ownership on Native Nations. The federal government unilaterally broke up communally held Reservation lands into individual allotments, or parcels. Some were allotted to Tribal families. Some were sold off to settlers.

Line 5 crosses numerous parcels within the Bad River Reservation, some owned by the Band (held in trust by the U.S. government), some owned by individual Tribal members, and some owned by non-Indians.

The Band negotiated a 50-year easement for Line 5 to cross its lands. In return, Enbridge paid it $800,000.

The BIA questioned the wisdom of such a long lease. It negotiated a separate 20-year easement on behalf of Indigenous owners of individual parcels within the Reservation. That agreement said that at the end of the 20 years, Enbridge “shall remove all materials, equipment and associated installations within six months of termination, and agrees to restore the land to its prior condition.”

Here’s where it gets complicated.

In the intervening years, the Band acquired additional lands along the pipeline corridor. This was the result of a federal law passed in 1982 to help Tribal Nations recover lands within their historic Reservation boundaries — the parcels that had been sold off through allotments.

Between 1994 and 2013, the BIA helped Bad River acquire ownership interests in 12 of the 15 parcels in the pipeline corridor for which the BIA had issued 20-year easements. “The Band presently owns 100% of two of the parcels and more than 45% fractional ownership in the remaining 10.”

The Band says ‘No’

By 2013, the Band owned some parcels with 50-year easements, and some parcels with 20-year easements.

An oil spill on the Reservation ‘would be catastrophic’ and would ‘nullify our long years of effort to preserve our health, subsistence, culture and ecosystems…'”

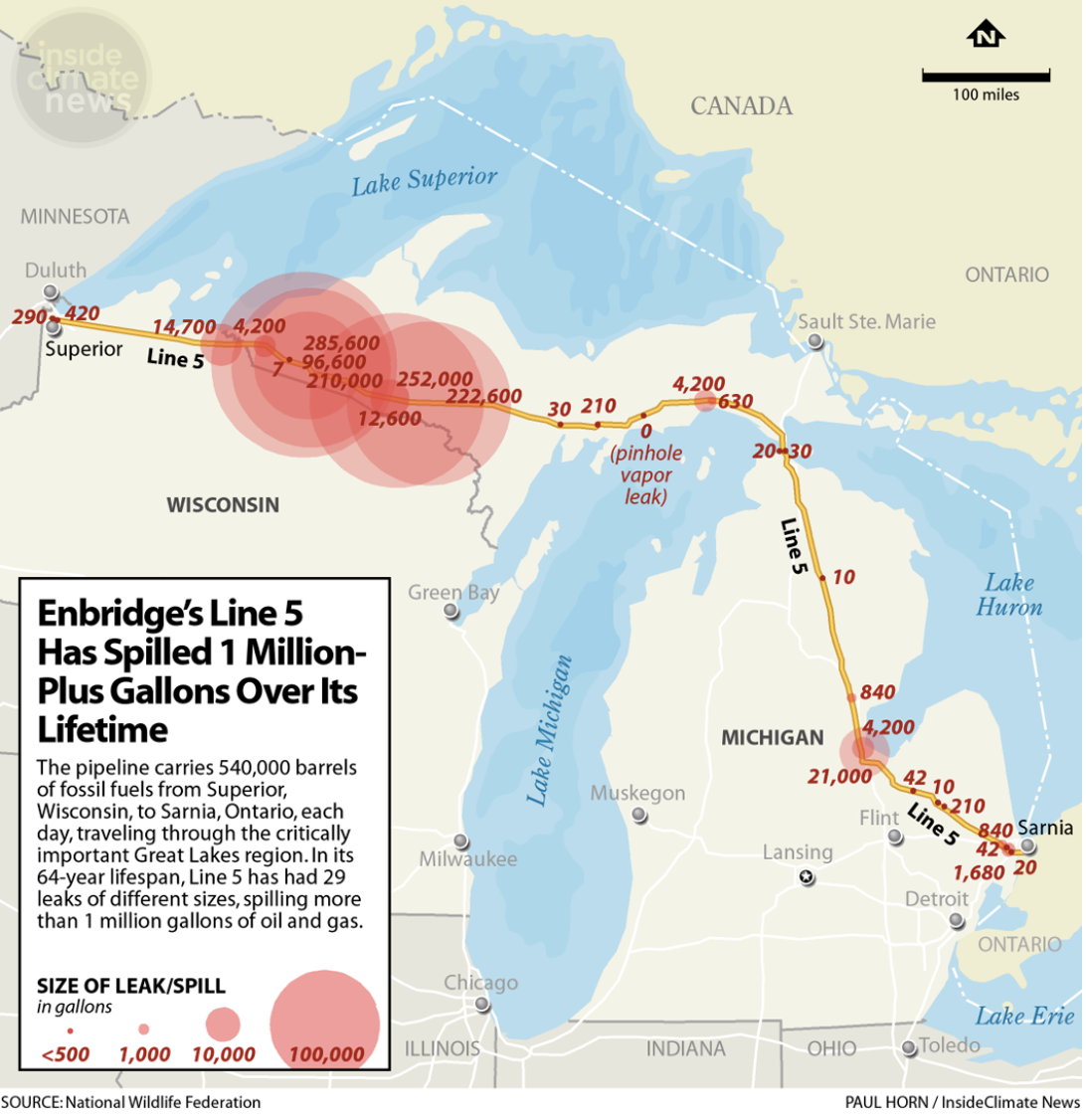

By 2013, Bad River had grown increasingly worried about the potential environmental harms Line 5 could create. Enbridge’s massive 2010 crude oil spill near Michigan’s Kalamazoo River was warning enough. It released more than 1 million gallons of crude and took years to clean up.

Bad River refused to renew Line 5 easements on the individual parcels it had acquired with 20-year easements. On Jan. 4, 2017, it passed a resolution stating its unwillingness to grant new easements.

“That resolution asserted that: the lands, rivers and wetlands in the Bad River and Lake Superior watersheds were sacred to the Band; an oil spill on the Reservation ‘would be catastrophic’ and would ‘nullify our long years of effort to preserve our health, subsistence, culture and ecosystems…'”

In spite of the resolution, Enbridge refused to remove the pipeline from Reservation lands, and continued to operate Line 5.

Enbridge’s arguments

Enbridge made several arguments saying the Band was required to extend the easements. The Judge rejected them all.

For instance, Enbridge argued the Band had to renew the 20-year easements because such an agreement was implied by the earlier 50-year easement the two sides negotiated for different parcels. The Band had an “implied duty of good faith and fair dealing” under Wisconsin common law, it said

The Band argued “the implied duty of good faith does not require it to give up its sovereign power to control its territory.”

The Judge said Enbridge’s efforts to cover all Band-owned lands under the 50-year easement “rely on a strained and unpersuasive reading of the 1992 Agreement.”

How to calculate unjust enrichment

Enbridge argued that if the Band’s trespass claim succeeded (which it did) the Band “is entitled to fair market rental value on the expired easements.”

The Band argued that “the rental value of the easement would not be a sufficient damage award.”

The Judge agreed, writing that Indian landowners are entitled, “under federal common law, ‘to an accounting of defendants’ profits from the operation of their pipeline and recovery of the pro-rata share

of those profits that is attributable to the portion of the pipeline that has been located on their property.'”

The court is persuaded that restitution or a profits-based remedy is appropriate and necessary in this case, both to address the violation of the Band’s sovereign rights and to take away what otherwise would be a strong incentive for Enbridge to act in the future exactly as it did here.

Judge Conley

The court is examining several issues, including “how the appropriate measure of past and future rent and damages to the Band should be determined.”

Reprinted with permission from the author Scott Russell. https://healingmnstories.wordpress.com/